Distinguished figures who (in addition to Dr. Elemér Hantos) have made a major contribution toward the promotion of economic cooperation worldwide:

Pál Auer (1885-1978), Hungarian lawyer, politician and diplomat.

After studying Law at the University of Budapest, and visiting Vienna, Berlin, Paris and London, Pál Auer successfully passed the bar exam in 1911. Subsequently, he opened his office in Budapest and specialized in International Law. Following the collapse of Austria-Hungary at the end of the First World War, Auer was a member of Mihály Károly's National Council. After a period of political instability in Hungary, during which he lived in Vienna, Auer returned to Budapest. In 1921, he was appointed legal adviser to the French legation in Hungary. In this capacity, he participated “discreetly in the evolution of official Franco-Hungarian relations” in the 1920s and 1930s.

During the interwar period, Pál Auer participated in the activities of the Paneuropean Union, presided by the Count Richard Coudenhove-Kalergi. From 1930, he was the President of the Hungarian section of the Paneuropean Union. Like Elemér Hantos, Auer was also in favor of deepening economic and political cooperation between the successor states of Austria-Hungary. That is why he organized a Danubian conference in Budapest in February 1932.

Following this conference, he presided the Committee for the economic rapprochement of the Danubian countries. For him, a “Danubian confederation” was particularly important to prevent the annexation of Austria by Nazi Germany. After the Second World War, Pál Auer became a member of the Hungarian Parliament and the President of its Foreign Affairs Committee. In March 1946, Auer was appointed Head of the Hungarian legation in Paris. Following the Communist seizure of power in 1947, Auer was “forced to choose exile” and stayed in Paris, where he remained a “mediator between Central Europe and France”. Auer was also very active in the European Movement, initiated by Winston Churchill. Until his death, he defended the concept of a “Danubian confederation”.

Click here for author credit, source materials and photo credit.

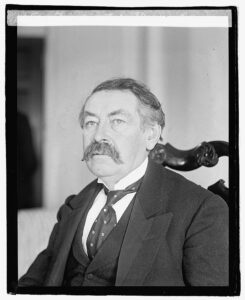

Aristide Briand (1862-1932), French lawyer, journalist, politician and Nobel Peace Prize laureate.

After studying Law at the University of Paris, Aristide Briand started his professional career as a lawyer and journalist. In 1902, Briand became a member of the Chamber of Deputies of the French Parliament. After having successfully defended the Law on the Separation of the Churches and the State in 1906, he served as Minister in various governments and was also appointed Prime Minister on several occasions before and during the First World War.

After the war, Aristide Briand became France’s permanent delegate to the League of Nations. From 1921 to 1922, Briand was Prime Minister with the portfolio of Foreign Affairs. From 1925, he did not leave the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs until 1932, shortly before his death, due to health problems. As the French Foreign Minister, Aristide Briand was the architect of the Locarno Agreements, signed in October 1925, which helped to ease Franco-German relations and to stabilize the post-war European political order. For this reason, Briand was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in December 1926, together with his German counterpart Gustav Stresemann. After the signing of the Briand-Kellog Pact in August 1928, which “outlawed war”, he envisaged the economic and political unification of Europe as the next step in his system of collective security in Europe. In this sense, he supported pro-European organizations, such as the Pan-European Union of Count Richard Coudenhove-Kalergi and the French Committee of the European Customs Union.

In September 1929, Aristide Briand announced his desire to create “a kind of federal bond” between the European peoples in a speech addressed to the General Assembly of the League of Nations. Elemér Hantos believed that “it [was] the idea of the economic unity of Europe and not that of a political Pan-Europe that emerge[d] from Briand’s speeches”. That is why Hantos was disappointed when Briand’s memorandum, presented in May 1930, consecrated the primacy of politics over economics.

Following the announcement of the Austro-German customs union project in March 1931, which marked a turning point in German foreign policy, Aristide Briand presented Elemér Hantos’s memorandum on the economic reorganization of Central Europe to the Study Commission for the European Union of the League of Nations in September 1931.

Click here for author credit, source materials and photo credit, and here for biography in Wikipedia.

Richard Coudenhove-Kalergi (1894-1972), Austrian philosopher and politician.

After receiving his doctorate in Philosophy at the University of Vienna in 1917, Richard Coudenhove-Kalergi developed his Pan-European idea in several newspaper and journal articles. In his programmatic book Pan-Europa, published in Vienna in 1923, Coudenhove-Kalergi called for the political and economic unification of the European states, except for Turkey, the British Empire and Soviet Russia. In the economic part of his program, he advocated the establishment of a Pan-European economic area by removing all economic, customs and transport barriers between the European states. Coudenhove-Kalergi considered that the economic unification of Europe could only be achieved gradually. In this sense, he envisaged the formation of economic, customs and monetary alliances between several countries, such as the Successor states of Austria-Hungary, which he specifically mentioned in his programmatic book, as a first step towards a Pan-European Economic Union.

To promote his Pan-European idea, Richard Coudenhove-Kalergi founded the Pan-Europa Union in Vienna which had national and local sections throughout Europe, published numerous articles, negotiated with political leaders and regularly organized Pan-European conferences and congresses. After the annexation of Austria by Nazi Germany, Coudenhove-Kalergi went into exile in Paris and later in New York. After the Second World War, he inspired Winston Churchill’s famous “Zurich speech” and participated in the European Movement. For his commitment of over twenty-five years to the political and economic unification of Europe, Coudenhove-Kalergi received the first international Charlemagne Prize of the city of Aachen in 1950.

Click here for author credit, source materials and photo credit, and here for biography in Wikipedia.

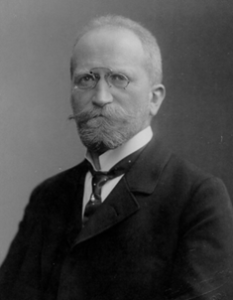

Georg Gothein (1857-1940), German engineer, politician and economist.

After his studies at the University of Breslau (today Wrocław) and at the Prussian Mining Academy in Berlin, Georg Gothein started his career as a Mining officer in Silesia and later also worked as Legal Advisor to the Chamber of Commerce in Breslau. Thanks to "his outstanding abilities, which were always employed in the spirit of liberalism and free trade“, Gothein entered the Prussian House of Representatives in 1893 and the German Imperial Assembly in 1901. After the First World War, he was not only a Member of the German National Assembly until 1924, but also briefly Minister without Portfolio and Treasury Minister in 1919, before he left the German government after the ratification of the Treaty of Versailles.

As a free trade advocate, Georg Gothein participated in the activities of the German Trade Agreement Association and the German Free Trade League, which was founded in November 1921, and presided the “German Group” of the Central European Economic Congress from 1926 to 1930. In this capacity, he criticized the Central European project of Elemér Hantos, who advocated an economic rapprochement between the Successor states of Austria-Hungary, for excluding Germany. Gothein was a strong advocate of the economic attachment of Austria to Germany, which he regarded as the only possible path towards the realization of a “Greater Central Europe” or an Economic Pan-Europe. Hantos was opposed to the economic and political attachment of Austria to Germany, because he feared the economic and political predominance of Germany and wanted the Successor States to be able to negotiate as more equal partners.

Click here for author credit, source materials and photo credit, and here for biography in Wikipedia.

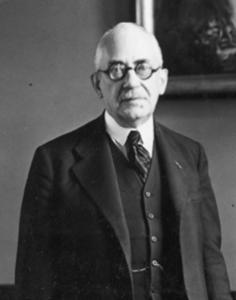

Gusztáv Gratz (1875-1944), Hungarian journalist, economist, politician and diplomat.

After receiving his doctorate in Political Sciences at the University of Budapest in 1898, Gusztáv Gratz started his career as a journalist. Later, in 1906, he became a Member of the Hungarian Parliament as a representative of the Transylvanian Saxons.

In 1912, Gratz took up the position of managing director of the Hungarian Association of Factory Industrialists. During the First World War, he was particularly active in the Central European movement, which promoted the idea of an economic rapprochement between Germany and Austria-Hungary. He was trying to find a formula “that would provide some protection for the Hungarian industry within the [German-Austro-Hungarian] economic alliance”. In 1917, he was named head of the Foreign Trade Section of the common Foreign Ministry of Austria-Hungary in Vienna. After a change of government in Hungary, he was shortly Finance Minister, before returning to his position at the Foreign Ministry. From 1917 to 1918, he participated not only in the economic negotiations with Germany about a Central European economic union, but also in the peace negotiations in Brest-Litovsk and Bucharest.

After the collapse of Austria-Hungary and the political instability in Hungary, which followed the First World War, Gusztáv Gratz was appointed Hungarian Ambassador in Vienna, before becoming Hungarian Foreign Minister in January 1921. In this capacity, Gratz envisaged economic and political cooperation between the Successor states of Austria-Hungary to stabilize the region within the new international order. After supporting the two failed restauration attempts of the former King of Hungary Charles, Gratz was sidelined from Hungarian politics. In 1926, he reentered the Hungarian Parliament as a representative of the German minority in Hungary.

From 1925, Gusztáv Gratz was the editor of the Hungarian Economic Yearbook, which presented an overview of the economic situation in Hungary after the disintegration of the economic area of Austria-Hungary. Like Elemér Hantos, Gratz advocated an economic rapprochement between the successor states of Austria-Hungary as the first step towards an European Economic and Customs Union and participated in the activities of the Central European Economic Congress and the Pan-European Union. From 1930, he was the president of the Central European Institute in Budapest, founded by Elemér Hantos.

Click here for author credit, source materials and photo credit, and here for biography in Wikipedia.

Milan Hodža (1878-1944), Slovak journalist, historian and politician.

After studying Law in Kolozsvár (today Cluj-Napoca) and Budapest, Milan Hodža started his professional career as a journalist. In 1905, he was elected Member of the Hungarian Parliament in Budapest, as representative of the Slovaks and the Serbs of the Banat region. During his mandate, Hodža advocated cooperation between the Slovaks and the Czechs, and created the “nationalities club”, which gathered Slovak, Serbian and Romanian Members of Parliament. At that time, he was also a member of the “Belvedere Circle” of Archduke Franz Ferdinand, the heir to the throne, and worked on the transformation of the Habsburg Monarchy into a federation of nation states. During the First World War, he completed his doctorate in Philosophy at the University of Vienna.

After the collapse of Austria-Hungary, Milan Hodža was involved the creation of the new Czechoslovak state and became the representative of the Czechoslovak government in Budapest. From 1920, Hodža was a Member of the Chamber of Deputies of the Czechoslovak Parliament for the Agrarian Party. In 1921, he was also appointed Professor in History at the University of Bratislava. During the interwar period, he was Minister on several occasions: Minister of Agriculture from 1922-1926 and from 1932 to 1935, as well as Minister of Education from 1926 to 1929.

As Minister of Agriculture, Milan Hodža wanted to solve the Central European agricultural crisis by promoting economic cooperation between the Successor states of Austria-Hungary. After Adolf Hitler’s rise to power, Hodža was a strong advocate of economic rapprochement between the Danubian states, in line with the ideas of Elemér Hantos. As President of the Czechoslovak government from November 1935, with the Portfolio of Foreign Affairs, he strove, in vain, to reach an agreement with the other Successor States of Austria-Hungary.

After the Munich Agreement in September 1938, as his government was forced to resign, Milan Hodža went into exile in Switzerland, later in France and in the United Kingdom, and finally in the United States, where he published his famous book Federation in Central Europe: Reflections and reminiscences in 1942.

Click here for author credit, source materials and photo credit, and here for biography in Wikipedia.

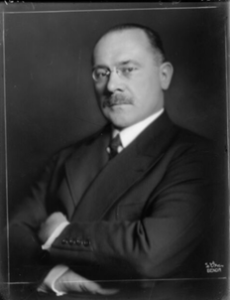

Rudolf Hotowetz (1865-1945), Czech economist and politician.

A few years after the completion of his doctorate in Law at the Czech University in Prague, Rudolf Hotowetz started to work at the Chambre of Commerce of Prague, “where he gradually rose to the place of its Secretary General” and greatly contributed to its excellent reputation. In 1917, after years of preparatory work, he was named President of the newly created General Pension Institute.

After the collapse of Austria-Hungary, and the creation of Czechoslovakia, Rudolf Hotowetz became President of the Foreign Trade Office and later Minister of Commerce. Hotowetz had to “cope with serious difficulties resulting from the separation of Czechoslovakia from the former economic unit”. With his colleague Václav Schuster, he was responsible for “the marking of the first lines of [the Czechoslovak] commercial policy and the conclusion of the first and most important commercial treaties” of the new Czechoslovakian state. In September 1921, Hotowetz resigned as Minister of Commerce to express his opposition to the new tariffs voted by the National Assembly.

From then on, Rudolf Hotowetz advocated economic rapprochement between Czechoslovakia and the other Successor states. Furthermore, he was also promoting the economic unification of Europe. In contrary to Richard Coudenhove-Kalergi, leader of the Pan-European movement, Hotowetz considered that Soviet Russia should be included in the European economic area. With the Austrian businessman Julius Meinl and the Hungarian economist Elemér Hantos, Hotowetz was one of the initiators of the first Central European Congress in Vienna in September 1925. He was also the Vice-President of the Czechoslovak Committee for Central European cooperation and the President of the Czechoslovak Section of the European Customs Union.

Click here for author credit, source materials and photo credit.

Walter Lippmann (1889-1974), American journalist, public philosopher and Pulitzer Prize winner.

After studying at Harvard University, Walter Lippmann began a career in journalism. In November 1914, he was one of the founding editors of the New Republic, in which he advocated the end of American isolationism. At the end of the First World War, Lippmann was “asked to join the staff of the Inquiry, a non-governmental and largely clandestine outfit that had been established […] to draw up American peace terms”. As its Secretary General, he participated in the drafting of Woodrow Wilson’s famous “Fourteen Points” program. After the First World War, Lippmann participated in the Paris Peace Conference as a member of the American delegation. Returning to the United States of America, he opposed the ratification of the Versailles Treaty which was, “to him, as to many others”, such as the British economist John Maynard Keynes, whom he had met in Paris, “a disillusioning experience”.

During the interwar period, Walter Lippmann became one of the most influential journalists and “columnists”, writing for the World and the Herald Tribune in New York, as well as a renown public philosopher. Following the International Economic Conference, which was held in London in June-July 1933, Lippmann started working on liberalism. His research led to the publication of "The Good Society" in 1937, which laid the foundations for the famous "Lippmann Colloquium”, which marked the renewal of liberal thought. In the aftermath of the Second World War, he expressed his support for the Marshall Plan for the economic reconstruction of Europe.

Click here for author credit, source materials and photo credit, and here for biography in Wikipedia.

Julius Meinl II. (1869-1944), Austrian businessman.

After his studies at the Vienna Business School and a brief stay in London, Julius Meinl started to work for his father’s food company. In 1913, following his father’s retirement, Meinl took over the company, which continued to expand under his leadership, despite the many economic and political difficulties of his time.

During the First World War, Meinl founded the Austrian Political Society with the Austrian Industrialist Max Friedmann. The Austrian Political Society gathered businessmen, professors and politicians to discuss political and economic issues. With the two Austrian jurists and politicians Heinrich Lammasch and Josef Redlich, he participated in peace talks with representants of the United States of America in 1917-1918.

After the First World War, Julius Meinl’s company suffered from the consequences of the disintegration of the economic area of Austria-Hungary. That is why, Meinl advocated the reestablishment of free trade within the Successor states. In 1924, Meinl founded the Austrian Free Trade League to fight against the new increased customs tariff planned by the Austrian government. In the capacity, Meinl invited other free trade advocates, such as Václav Schuster, Elemér Hantos and Rudolf Hotowetz, to give conferences. Together, they initiated the first Central European Economic Congress in Vienna in September 1925, with the intention of working towards an economic rapprochement between the Successor states of Austria-Hungary.

Click here for author credit, source materials and photo credit, and here for biography in Wikipedia (in German}.

Ludwig Mises (1881-1973) was an Austrian economist.

After obtaining his doctorate in Law at the University of Vienna, where he studied Economics, Ludwig Mieses entered the service of the Chamber of Commerce of Vienna in 1909. Before the First World War, Mieses habilitated in Economics and started teaching at the University of Vienna, where he became Professor in 1918.

In September 1925, Ludwig Mises participated in the first Central European Economic Congress. From 1928, he was also a member of the International Committee of the European Customs Union. Following the publication of one of Elemér Hantos’ books in which he presented the economic unification of the successor states of Austria-Hungary as the first step towards a European customs and economic union, Mises resigned in March 1929, considering it impossible for him to participate in organizations that opposed the economic attachment of Austria to Germany. However, after the rise of National Socialism in Germany, he participated in the Pan-European Economic Conferences organized by Count Richard Coudenhove-Kalergi.

In 1934, Ludwig Mises was invited by William Rappard to take on a Guest Professorship at the Graduate Institute of International Studies in Geneva. In 1940, he emigrated to New York, where he continued his scientific work during and after the Second World War. Ludwig Mises was known as a “leading representative” of economic liberalism.

Click here for author credit, source materials and photo credit, and here for biography in Wikipedia.

Jean Monnet (1880-1979), French businessman, international civil servant and politician.

Jean Monnet left high school before graduating to work in the family cognac business, for which he traveled the world. During the First World War, Monnet participated in the organization of the war economy, more specifically in the coordination of Franco-British supply efforts in London.

In the aftermath of the war, Monnet was named Deputy Secretary-General of the League of Nations. In this capacity, he organized the International Financial Conference which was held in Brussels in September 1920. He also participated in several missions of the League of Nations, before resigning in December 1922, to work on reorganizing the struggling family cognac business. From 1926, Monnet started a career as an international banker.

Returning to France at the dawn of the Second World War, Monnet participated in the preparation and coordination of the Franco-British and transatlantic armament effort. After the German troops entered Paris in June 1940, he supported the Franco-British Union project. After the fall of France, Monnet was sent to the United States by the British government to negotiate the purchase of war supplies and helped coordinate their war efforts.

After the Allied intervention in French North Africa in November 1942, Monnet took part in the negotiations which led to the creation of the French National Liberation Committee. In Algiers in 1943, he began to think about post-war European unification. As the French Planning Commissioner after the Second World War, Jean Monnet oversaw the economic reconstruction of France. He worked “in the shadows” for the economic unification of Europe and wrote the famous “Schuman declaration” presented on May 9, 1950, which is considered the starting point of the so-called “European construction”.

During the negotiations on the treaty establishing the European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC), Jean Monnet proposed the creation of the European Defense Community (EDC) to the French President of the Council, René Pleven. After the Treaty of Paris came into force in July 1952, Monnet became the first President of the High Authority of the ECSC. The treaty establishing the EDC was signed in Paris in May 1952 by the governments of the six founding member states of the ECSC, but Monnet’s initiative failed in August 1954, because the French National Assembly did not ratify the treaty.

After his resignation, Monnet set up his Action Committee for the United States of Europe, in order to participate in the creation of favorable conditions for deeper European economic integration. With his committee, Monnet campaigned for a nuclear energy community and a single market during the European “relaunch” led by the Dutch and Belgian governments from 1955 onwards. The “relaunch” led to the signing of the Treaties of Rome in March 1957, which established the European Economic Community and the European Atomic Energy Community.

Click here for author credit, source materials and photo credit, and here for biography in Wikipedia.

William Rappard (1883-1958), Swiss historian, economist and international civil servant.

After receiving his doctorate in Law from the University of Geneva, he started his professional career in 1909 as a secretary at the International Labor Organization, based in Basel. After a few years of teaching, he was appointed Professor at the University of Geneva in 1913, where he also held the position of Rector from 1926 to 1928 and from 1936 to 1938. In 1928, he founded the Graduate Institute for Advanced International Studies in Geneva, which he directed until 1955. From 1920 to 1925, Rappard also worked for the League of Nations.

Throughout the 1930s, William Rappard “denounced the threat to peace posed by political and economic nationalism” and was an advocate of a united Europe. As the Director of the Graduate Institute, he invited Elemér Hantos to give a series of conferences on Central Europe in 1930.

Click here for author credit, source materials and photo credit, and here for biography in Wikipedia.

Václav Schuster (1871-1944), Czech economist, politician, diplomat and banker.

After completing his doctorate in Law at the Czech University in Prague, Václav Schuster entered the service of the Chamber of Commerce in České Budějovice, before starting to work at the Chamber of Commerce in Prague, where he succeeded Rudolf Hotowetz as Secretary General in 1917.

After the collapse of Austria-Hungary, and the creation of the Czechoslovakian state, Václav Schuster became Secretary of State at the Ministry of Trade and later participated as Envoy extraordinary and Minister plenipotentiary in the trade negotiations with the Great powers and the other Successor states. In this capacity, Schuster greatly participated in shaping the Czechoslovak trade policy. For a journalist of the German newspaper Prager Presse, supported by the Czechoslovak government, “he will be remembered for his clear-eyed and courageous opposition to the immediately emerging radicalism in trade policy, even at the risk of having his [Czech] patriotism called into question”. From 1922, Schuster was the President of a Czech Bank, while being a member of the executive boards of numerous private companies, public institutions and associations.

“With a keen eye”, Václav Schuster recognized “earlier than anyone else the practical importance of the [economic] unification movements […] when this goal still seemed to be a nebulous utopia”.

Like Elemér Hantos, Schuster advocated an economic rapprochement between the Successor states of Austria-Hungary as the first step towards the economic unification of the entire European continent. He was the President of the Czechoslovak section of the Pan-European Union and also participated in the activities of the Czechoslovak Committee for Central European Economic Cooperation, the Czechoslovak section of the European Customs Union and the Central European Institute in Brno.

Click here for author credit, source materials and photo credit.